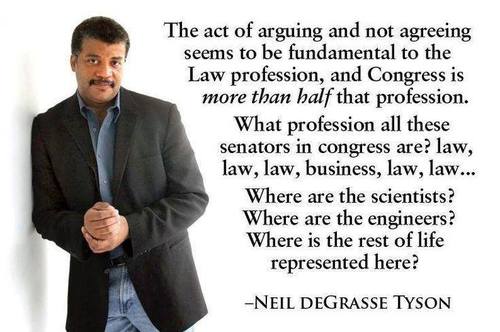

Tyson asked this question on Real Talk with Bill Maher back in 2011; but he was not the first to ask and I suspect no answers will be forthcoming.

Discussing diversity and the relationships between social location, experience, and decision-making perspective seems to be one of the quickest ways to make lots of people uncomfortable. Just last week I read a report on a theological seminar held at a local Adventist university. The writer informed us that there were “about 170 attendees” and that “several [Adventist] General Conference leaders, including representatives from the vice presidential circle, the Biblical Research Institute and the Adventist Review, were present.” I wasn’t sure what meaning to assign this information, so I went back and reviewed the content of the article, the photographs of the room, and the attendee information provided. And then I asked:

Can anyone who was present share how many of the central discussants and conversants were female, non-White, non-American, or under the age of 35? Since the event was hosted by WAU, was it also patronized by WAU students? If so, how engaged were they with the presentations and responses? Did you sense that they felt any ownership of or responsibility for the story Brueggemann and other named speakers wove? (x)

So far my only feedback has been a thumbs down. Perhaps I’m not supposed to ask these questions about a public event held at a university. Perhaps it’s not supposed to matter if speakers and active participants in a theological conversation are all male, and all, apparently, over 40 years old. Perhaps we are still that naive.

Tyson’s question about the composition and disciplinary skew of Congress also applies outside politics. The collective that frames, writes, and presents theology and philosophy shapes the stories religious communities tell about their scriptures, beliefs, purpose, history, and relationship with the world beyond the gate. Its composition isn’t neutral.

Millennials and other young adults are disproportionately exiting or losing confidence in environments that don’t seem to understand that social location and experience shape and limit perspective, that visibility matters, and that invisibility marginalizes. Neither the political realm nor the religious communities can afford to dodge this, not during the election cycle, not in decision-making committees, not in public ministry, and not on college campuses.

Who speaks for the people who aren’t invited to speak? How will the invited audiences hear them? And how will their absence skew the stories told?

In Case You Missed It: Check out and contribute to Tara L. Conley’s Millennial Manifesta. While focused on economic and labor injustices, Conley is also concerned that Millennials have no peers among current members of Congress and no bloc means of insisting on accountability based on their actual interests or needs.

Today, she shared a quote from Carole Pateman’s classic book on participatory democracy (1970). Whereas some ’70s theorists claimed that citizen apathy kept a system stable, and 1980s theorists thought participatory models quaint and “outmoded,” Pateman argued for engaged citizenship. She has evolved beyond the raw populism that was au courant in the 1970s, but continues to advocate for a space beyond deliberation for ordinary citizens in the routine political spaces that affect us all.

The [empirical] findings show that ordinary citizens, given some information and time for discussion in groups of diverse opinions, are quite capable of understanding complex, and sometimes technical, issues and reaching pertinent conclusions about significant public matters. Moreover, they have to justify their reasoning in their reports. These empirical findings provide a valuable counterweight to the poor opinion of ordinary citizens found in much political science, and to the frequently heard view that many, perhaps even most, matters of public policy are best left to, or must be left to, experts.